In the early 90s, the golden age of electronic music was in full swing, harmoniously filling airwaves from Europe to North America.

Amid this, a singular event in British history often seems to skip unnoticed by many, except perhaps the most ardent electronica fans – that is the curious case of Autechre’s Flutter Vs The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994.

The Criminal Justice Act was a landmark piece of legislation passed by the UK government in ’94 to exert control over all sorts of public gatherings, including raves, an integral part of global youth and music culture.

In response to the Act’s specified regulations on music, vehement opposition flowed from various quarters within the industry, and Autechre’s album ‘Flutter’ became an infamous sonic manifestation against it.

The Rave Epidemic that Shaped 80’s & 90’s UK

In the 80s and 90s, the UK was all set ablaze by the ‘Rave Epidemic.’ This brightly colored, glowstick-waving wave took over warehouses, fields, and abandoned spaces across the nation with impromptu parties fuelled by ecstatic dance music and an ethos of unity.

The Phenomenon That Was Rave

The rave phenomenon can be hard to define, but it essentially revolved around underground electronic dance music gatherings – often illegal.

These were not your average parties; they could last up to 24 hours, attracting crowds of thousands.

Raves were musical beacons of diversity integrated with a do-it-yourself, anti-establishment attitude.

Sound of a Revolution

Emerging from Chicago’s house scene and Detroit’s techno revolution in the mid-’80s, acid house became hugely popular across Europe.

Genres like breakbeat hardcore and jungle further diversified this new culture, emphasizing pulsating basslines, intricate breaks, and psychedelic atmospheres.

While this might seem like an idyllic development in cultural expression to some, it was not without its critics or controversies.

Some UK policymakers saw raves as lawless gatherings promoting drug use and antisocial behavior.

This perspective would lead to a significant change in legislation through none other than The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994.

Also Read: The Beatles And Klaatu 2025 [Top Songs of Klaatu]

Unpacking The Impact: The 1994 Criminal Justice & Public Order Act

In 1994, the UK government responded to the so-called ‘rave epidemic’ by passing legislation that continues to impact music and culture today.

The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994 specifically targeted raves with laws designed to curtail these gatherings.

Groundbreaking Legislation

Within this substantial act, one specific clause left a lasting imprint on UK music culture.

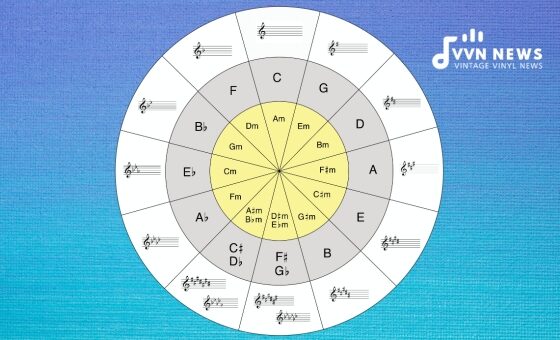

It sought to define ‘music’ as sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by “the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

The implications were profound. It meant that law enforcement could halt events featuring such music if they even suspected it could lead to disorder.

It was no longer just illegal raves under threat; even sanctioned events could be shut down.

Battle with Culture

The act faced fervent criticism for stifling cultural expression and freedom.

Critics argued that it discriminated against specific cultural sectors while highlighting authorities’ ignorance towards burgeoning electronic music genres.

Many from the music industry and beyond rose against this restrictive legislation. Still, one group brought an innovative, thoughtful response to their protest – an electronic band named Autechre challenged this act with their politically significant album ‘Flutter’!

This clash between Autechre’s Flutter vs The 1994 Criminal Justice & Public Order Act has since become part of electronic folklore, pitting artistic innovation against state regulation in a standoff that continues to fascinate fans and scholars alike.

In our next segment, we will delve deeper into Autechre’s rebellious response. How did they challenge authority while adhering to the rules? Let’s find out!

Autechre’s Flutter: Challenging the Law

Autechre, a pioneering electronica duo from Manchester, England, played a significant role in challenging the Criminal Justice Act of 1994 through their ingenious composition.

Their strategy was musically bold and brilliant. A specific track on their album ‘Anti,’ titled ‘Flutter,’ was explicitly designed for dancing around the law’s restrictions.

Making Sense of Section 63

To understand Autechre’s strategy, we must delve into Section 63(1)(b) of the Criminal Justice Act.

This section sought to grant police powers to remove persons attending or preparing for a ‘rave’ – gatherings where music “includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

The aim? To squelch parties dominated by rhythmic electronic music. However, lawmakers had not anticipated how craftily artists could avoid such presets.

The Beauty of ‘Flutter’

In response, they constructed ‘Flutter’ – a brilliant masterpiece lasting approximately ten minutes. It was ingeniously engineered such that no bar consisted of repetitive beats.

Despite being entirely within the established genre standards, each beat throughout all four tracks of the EP differed slightly from those before and after it. Thus, they were able to sidestep the exact wording of this law.

Campaigning Against Censorship

Copies of the album even came with a disclaimer: “The programmed material does not contain repetitive beats.”

Through this singular musical rebel-yell ‘Flutter,’ Autechre sounded its campaign against musical censorship.

To this day, ‘Flutter’ is an inspiring reminder for many artists and fans about how creativity can defy constraints as stifling as a parliamentary order.

It marked an audacious musical reply to authority, unabashedly affirming the right to unrestricted musical expression.

‘Flutter’ was not just a piece of music; it was an act of resistance against an attempt to suppress a cultural revolution. And for that reason, its resonance echoes far beyond its composed chords and rhythms.

Also Read: Who Was Israel Kamakawiwo’ole? 2025 [The Music Of Hawaii]

Battle of the Beats: Autechre and Others Take a Stand

Many from the music industry made their stand in retaliation to the censorship of an entire counterculture.

High-profile figures within the scene rallied against the act, holding protests and creating art that opposed it. Among these voices of resistance, one British electronic duo stood out – Autechre.

A Silent but Sonic Protest

Renowned for their experimental ambiance and abstract sound, Autechre has always been a bold innovator within electronica.

However, in response to The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994, they took innovation to an entirely new level.

Flutter – An Album Like No Other

The duo’s fourth EP, ‘ Flutter’, was released as a direct response to this restrictive legislation.

Made up of three tracks and clocking just under 24 minutes, each track was artistically crafted by Rob Brown and Sean Booth (the duo behind Autechre) to retain a highly rhythmic yet unsettling sound.

Finding Loopholes

The genius behind Flutter wasn’t just in its musical composition but in how it navigated around the wording of The Criminal Justice Act.

The Act defined music as “sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

By ensuring that no more than eight bars had repeating beats throughout ‘Flutter’, Autechre could effectively sidestep the law.

Other artists joined this renegade movement, launching their musical protest against what they viewed as an unjust act aimed at suppressing cultural expression through music.

This audacious approach won plaudits across underground music communities worldwide and placed ‘Flutter’ as one of the most politically defiant albums ever among techno enthusiasts.

Also Read: Who Was The Fifth Beatle? [George, Ringo, John & Paul]

Outsmarting the System: Autechre’s Ingenious Strategy

Now and then, music becomes more than just an accessory to life. Becoming a sly force that silently but surely intrudes on the political landscape and leaves its mark in history.

This story of piercing rebellion is seen with the British electronic music duo Autechre and their album “Flutter,” which served as a sonic response to the Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994.

The Irresistible Charm of Subversion

Autechre took a unique approach to navigate the restrictions on repetitive beats laid out by subsection 63(1)(b) of the Act, which defined music as sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by repetitive beats.

This attempted to target rave parties, which featured prolonged electronic dance music sets that often had loops and repetitive patterns.

The ingenious strategy employed here wasn’t just about creating non-rhythmic noise or ditching recognizable musical structures.

Instead, Autechre crafted “Flutter” so that no bars contain identical beats – reaching out to their audience without being legally classified as repetitive.

Flutter: Did It Sound Different?

Did it make any difference compared to other electronic tunes of the era? Yes and no.

When played, ‘Flutter’ doesn’t abandon its musicality for protest’s sake; rather, it is full of melodic phrases and rhythmic variations that adhere to aesthetics widely loved in electronic genres.

To an ordinary listener who may not be intent on analyzing each beat, it feels as immersive and groovy as any other contemporary classic.

Jukin’ The Stats

A clever reminder included with ‘Anti EP’, where ‘Flutter’ was released, said: “Warning! Lost & Djarum contains repetitive beats. We advise you not to play these tracks if the Criminal Justice Bill becomes law.’

‘Flutter’ has been programmed so that no bars contain identical beats and can therefore be played at both +8 or -8 without losing the structure of the music”.

Thus, beyond their exemplary body of work, Autechre will remain remembered as those who brilliantly blurred the lines between protest and art, thumbing their musical noses at the establishment in a truly innovative way.

Clash of Controversies: Autechre’s Flutter vs. The 1994 Criminal Justice & Public Order Act

In reaction to the uncontrollable rave culture, the UK government passed The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act in 1994.

This legislation had sweeping changes that significantly impacted society, including public protests and squatters.

But perhaps its most surprising inclusion regulated the music played at raves.

For the first time in history, a style of music was codified in law, specifically targeted towards gatherings defined by their “repetitive beats.”

A Controversial Clause

One particular clause in Section 63(1)(b) of the Act has sparked a great deal of controversy:

” Music includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

Ironically, encapsulating genres like techno and house into this legal definition, it was seen by critics as an attack on youth culture and freedom – a battle between government authority and personal liberty.

Musical Resistance

Enter Autechre (pronounced “awe-the-ker”), an experimental electronic music duo who responded to this ruling with one powerfully defiant album – ‘Anti.’

Particularly captivating is their groundbreaking track ‘Flutter,’ metaphorically extending a middle finger to this clause.

Flutter breaks up its beat patterns so ingeniously that it outwitted even such precise legislation.

Ingenious Strategy

While avoiding repetitive successions or beats as per the Act’s definition, Autechre creatively rearranged and reorganized beat sequences enough so that no section is melodically identical during its composition.

This cryptogrammatic breaking up of sequences meant ‘Flutter’ could legally be played at any rave without breaching conditions specified by the Act – while still retaining an engaging tempo for dancers.

The curative power wielded by music is no secret. But who would have thought that an abstract piece such as ‘Flutter’ would be such a fantastic historical example of this power?

It challenged oppressive legislation, becoming an unconventional beacon of protest through beats and tempo.

A Ripple Effect

Undeniably, the ripple effect caused by Autechre’s Flutter was immense. It encouraged other artists to experiment with the format of their music to avoid falling foul of Section 63(1)(b) and further redefined the boundaries of electronic music.

FAQs About Autechre’s Flutter vs the Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994

What essentially was the Rave phenomenon in the 80s and 90s?

The rave phenomenon was typified by underground gatherings centered around electronic dance music, frequently staged illegally and can last up to 24 hours.

How did the sound of this rave revolution shape up?

Emerging from Chicago’s house scene and Detroit’s techno revolution, acid house became popular across Europe, with genres like breakbeat hardcore and jungle diversifying this new cultural vibe.

What led to drafting The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994 in the UK?

Rising concerns over raves being seen as lawless gatherings promoting drug use and antisocial behavior triggered the drafting of The Criminal Justice & Public Order Act

How does Autechre’s Flutter relate to The Criminal Justice Act of 1994?

Autechre’s album ‘Flutter’ is seen as a sonic opposition to that Act’s specific music regulations

How has Autechre’s Flutter been perceived within popular culture?

Some saw Autechre’s Flutter as an ingenious strategy, creating beats that went against the law without breaking it.

Conclusion

Autechre’s Flutter not only challenged the constraints of the Criminal Justice & Public Order Act of 1994, it also highlighted the power of music as a form of protest.

Artists, including Autechre, resisted regulation and defended culture’s right to evolve organically and unhindered.

This acted as a reminder that music transcends entertainment; it is also an expression of individual liberty and societal shifts.

They proved that even amidst strict legislation, creativity can find its way and leave behind indelible influences within art scenes and industries.

Never underestimate the connection between music and freedom.