Music notation often feels like a secret code, with its clusters of lines, dots, and symbols that magically translate to melody and rhythm.

Among these notations is a simple yet crucial element known as “beaming in music.”

This graphical feature connects multiple musical notes, guiding performers on how to articulate the passage.

Understanding beaming not only helps in reading music more effectively but also in uncovering the nuanced decisions composers make to add character and direction to their compositions.

Beams do more than just tidy up sheet music; they provide significant insight into the tempo and feel of a musical piece.

A beam’s presence or absence can dramatically alter how a segment of notes is played, influencing everything from pace to accentuation.

While often overlooked, grasping the concept of beaming is vital for any musician looking to convey a piece’s intended emotion and energy.

Join me as we explore the intricacies of beaming in music and why it’s an essential part of interpreting and performing music with fidelity.

Different Note Values That Can Be Beamed

In the intricate language of music notation, beams connect certain note values that share a common rhythmic grouping.

The notes eligible for beaming are typically those shorter in duration, such as eighth notes (quavers), sixteenth notes (semiquavers), thirty-second notes (demisemiquavers), and even sixty-fourth notes (hemidemisemiquavers).

Here’s a quick rundown of these notes and their essential role in beaming:

- Eighth Notes (Quavers): With one flag when isolated, these can be beamed in groups to reflect the beat structure.

- Sixteenth Notes (Semiquavers): Featuring two flags, they’re often combined with eighth notes for rhythmical diversity.

- Thirty-Second Notes (Demisemiquavers): These speedier notes display three flags and are less frequently used but can still form part of a beam.

- Sixty-Fourth Notes (Hemidemisemiquavers): Although rare, four-flagged sixty-fourth notes may also be grouped under a single beam.

Beaming is not just about the aesthetics; it’s crucial for understanding rhythmic patterns and distinguishing between beats and sub-beats.

Uniting these shorter-value notes under beams shapes the phrasing and dictates a clearer sense of timing within a piece.

Also Read: Phrygian Mode [Adding Exotic Flair To Your Musical Compositions]

Beaming with Rests and Time Signatures

Beaming in music serves as a bridge that connects notes of shorter value, such as eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and so on.

When it comes to incorporating rests within a sequence of beamed notes, the principle is straightforward: rests cannot be beamed.

Instead, rests serve as separators between beamed groups within a measure. The time signature heavily dictates the position and frequency of these rests.

A time signature denotes how many beats are in each measure and which note value constitutes one beat.

In common 4/4 time, where there are four beats to a measure with the quarter note getting beat, you’ll often find two sets of eighth notes beamed together within one beat or all four sets within a full bar if uninterrupted by rests.

However, in 6/8 time, where the eighth note gets beat, beams can group six eighth notes to indicate two beats per group a reflection of this compound meter’s lilting characteristic.

Critical Insights into Various Time Signatures:

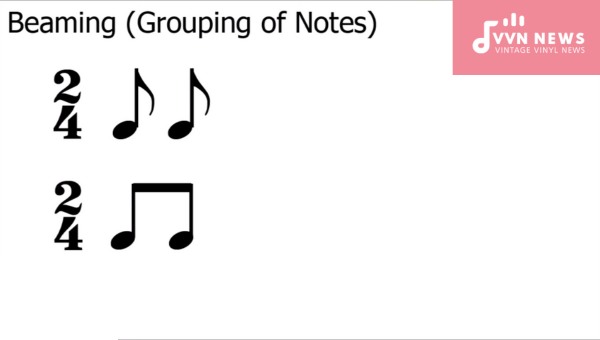

- 2/4 Time: You would expect to see single beams connecting pairs of eighth notes, each pair reflecting half a beat.

- 3/4 Time: Three-quarter note beats could have three sets of beamed eighth notes aligning with each quarter note beat.

- Complex Meters: For more complex or irregular time signatures like 5/8 or 7/8, beams help articulate subdivisions by grouping notes per the prescribed accent pattern (e.g., 2+3 for 5/8).

Understanding how beaming is adapted across different time signatures allows musicians to interpret rhythmic structures accurately and maintain cohesive timing throughout their performances.

What Determines the Direction of Stems in Beaming?

When you encounter a group of beamed notes in sheet music, one of the first things you’ll notice is whether the stems and the thin lines attached to the note heads are pointing upwards or downwards.

This direction isn’t arbitrary; it’s carefully chosen based on several factors that ensure musical clarity and aesthetic balance.

The Rules of Stem Direction:

Primarily, stem direction is governed by the position of the note head in relation to the middle line of the staff. Here are some key points:

- Notes Above the Middle Line: Typically, for notes placed above the middle line, stems will descend from the left side of each note head.

- Notes Below the Middle Line: For notes below this midpoint, stems usually ascend from the right side.

- Notes on the Middle Line: When a note rests exactly on that middle dividing line, other factors come into play, like surrounding notes or traditional stem direction for specific pitches (e.g., B in treble clef usually sports a downward stem).

Contextual Considerations:

However, it’s not just individual note positions that determine stem direction. The overall context and grouping of notes are also influential.

- Grouped Notes Spanning Both Sides: If your beam encompasses notes both above and below that middle threshold, musicians often look at where most notes lie or consider voice leading to decide stem direction.

- Multiple Voices: In music with multiple voices on a single staff, upbeams may represent one voice and downbeams another, aiding in visual separation.

Utilizing consistent rules for stem directions ensures your music is not only easy for performers to read but also maintains a clean appearance.

Also Read: Mixolydian Mode [Add Depth & Richness To Your Music Today]

How are Beams Angled in Music Notation?

In music notation, beaming refers to the practice of connecting eighth notes (quavers) and smaller note values like sixteenth notes (semiquavers) with a horizontal or diagonal line.

The angle of a beam is not arbitrary; it’s carefully crafted to reflect the melodic contour of the rise and fall of the notes it connects.

If a series of beamed notes move stepwise up or down, the beams slightly tilt to match this movement.

If the first note’s stem is on the right side and goes up, the beam angles upward; conversely, if it goes down, the beam slants downward.

However, for larger leaps or mixed stepwise and leaping motion within beamed groups, beams tend to remain more horizontal for readability.

Composers and engravers follow precise guidelines to ensure uniformity:

- Horizontal Beams: Common when notes are of consistent pitch.

- Diagonal Beams: Reflective of ascending or descending patterns.

- Beam Parallelism: Secondary beams maintain parallelism with primary ones.

When executed correctly, angled beams visually guide musicians through the flow of the music without crowding the stave or causing confusion.

Primary and Secondary Beams in Music Notation

In the musical stave, notes are connected by horizontal lines known as beams that replace individual note stems, reflecting the rhythmic grouping of notes.

Within this beaming structure, we encounter two types: primary beams and secondary beams.

Primary Beams

The primary beam is the first level of beam used to connect notes. It’s the thick, horizontal line that attaches to the note heads at their stem.

Notes sharing a primary beam are usually part of the same beat or sub-beat within a measure.

When you see eighth notes, sixteenth notes, or even smaller divisions linked together, it’s the primary beam that unifies them into comprehensible rhythmic units.

Secondary Beams

When dealing with smaller subdivisions like sixteenth notes or thirty-second notes, secondary beams come into play.

These are additional beams that attach below or above the primary beam. They help further delineate how these smaller note values are grouped within a piece’s rhythmical structure.

Understanding when to use secondary beams comes down to readability and musical phrasing—the goal is always clear communication of timing and rhythm for the performer.

Also Read: Aeolian Mode [The Secret To Creating Moody & Expressive Music]

How is Beaming Applied Specifically in 4/4 and 3/4 Time Signatures?

Beaming in music serves as a visual aid to group notes, making it easier for musicians to understand rhythmic patterns and phrase structure.

When it comes to common time signatures, such as 4/4 (four-quarter notes per measure) and 3/4 (three-quarter notes per measure), specific rules govern how beaming is used to reflect the natural pulse of the music.

In 4/4 Time Signature

The 4/4 time signature, often referred to as “common time,” has a strong sense of rhythm with two main beats per measure.

This duple pulse can be further subdivided into four quarter-note beats. Here’s how beaming is typically employed:

- Eighth notes are commonly beamed together in groups of two or four, reflecting the subdivision of each beat.

- Sixteenth notes might be beamed in groups of four, representing one full beat, or split into pairs to underscore the subdivisions.

- The beams should visually align with each quarter-note beat (i.e., not bridge over the strong-weak-medium-weak beats).

In practice:

- Strong beats: The first and third beats are primary, often starting a new group of beamed notes.

- Weak beats: The second and fourth are weaker; beams usually won’t cross these unless you’re dealing with syncopation or other stylistic choices.

In 3/4 Time Signature

The 3/4 time signature, known as waltz time, provides a different rhythmic feel more akin to a dance rhythm with one accented beat followed by two lighter ones. Beams here follow that waltz-like cadence:

- Groups of two or three eighth notes together, often just two eighth notes, are beamed since each represents half a beat.

- For sixteenth notes, we would see beams connecting either sets of four (for one full beat) or divided throughout the bar, reflecting each individual beat pattern.

Familiarize yourself with pieces in both meters and notice how composers use beams. It won’t just inform you but will enhance your performance, too.

What is Feathered Beaming and Its Purpose in Music Notation?

Feathered beaming is an expressive tool in music notation that denotes a gradual change in the speed of a series of notes, more specifically, an acceleration or deceleration.

When you come across feathered beams, you will notice that the beams are not evenly spaced. Instead, they start closely knit together and gradually spread out, or vice versa.

Key Characteristics of Feathered Beaming

- Acceleration: For an acceleration (accelerando), the beams will start close together on one side and fan out towards the other end.

- Deceleration: Conversely, for a deceleration (ritardando), the spacing between beams starts wider and converges to become narrower.

Purpose in Music Notation

The use of feathered beaming serves as a visual cue for musicians to either slowly speed up or slow down their playing over the course of the beamed notes.

Unlike specific tempo changes written with traditional notation (such as precise metronome marks), feathered beaming allows for a more fluid and organic change in pace that mirrors how a natural increase or decrease in tempo might feel.

Application

This technique is especially favored in avant-garde compositions and solo passages where composers seek to instill a sense of freedom and flexibility.

The lack of strict rhythmic value assigned to each note under a feathered beam indicates that it’s up to the performer’s discretion to interpret how gradually these tempo changes should occur.

Also Read: G Major Scales And Chords [Expand Your Musical Understandings]

FAQs on Beaming in Music

What is the role of beaming in music?

Beaming is used to connect multiple notes, indicating how a musician should perform them as part of a rhythmic grouping.

Can beams connect notes of different pitches?

Yes, beams can connect notes of varying pitches as long as they’re part of the same rhythmic grouping.

Is beaming used in non-percussive instruments like strings or wind instruments?

Absolutely, beaming affects articulation and phrasing on all instruments, not just percussion.

Does the length of a beam have any significance?

No, the length corresponds to the number of notes connected and doesn’t impact their duration or timing.

Why do some beams slope up while others slope down?

The direction of beams is generally determined by the position of the notes in relation to the middle line of the staff; it enhances readability.

Conclusion

Beaming in music notation is not merely a visual aid; it’s an essential tool that dictates the flow and feel of a piece.

By understanding its nuances, you can interpret musical directions with precision, ensuring each note you play or sing resonates with the composer’s intent.

From rhythmic accuracy to expressive performance techniques, mastery of beaming can truly enrich your musical experience.